Markov Chain Monte Carlo

Overview

Turn posterior sampling into Markov-chain design for cases where variational approximations fall short.

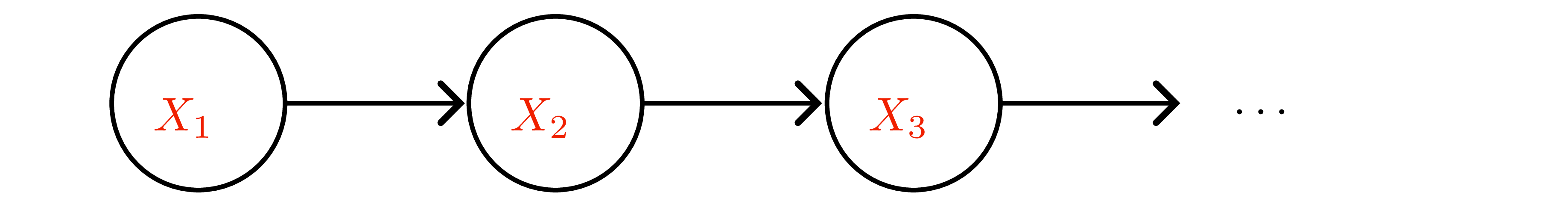

Markov-chain preliminaries

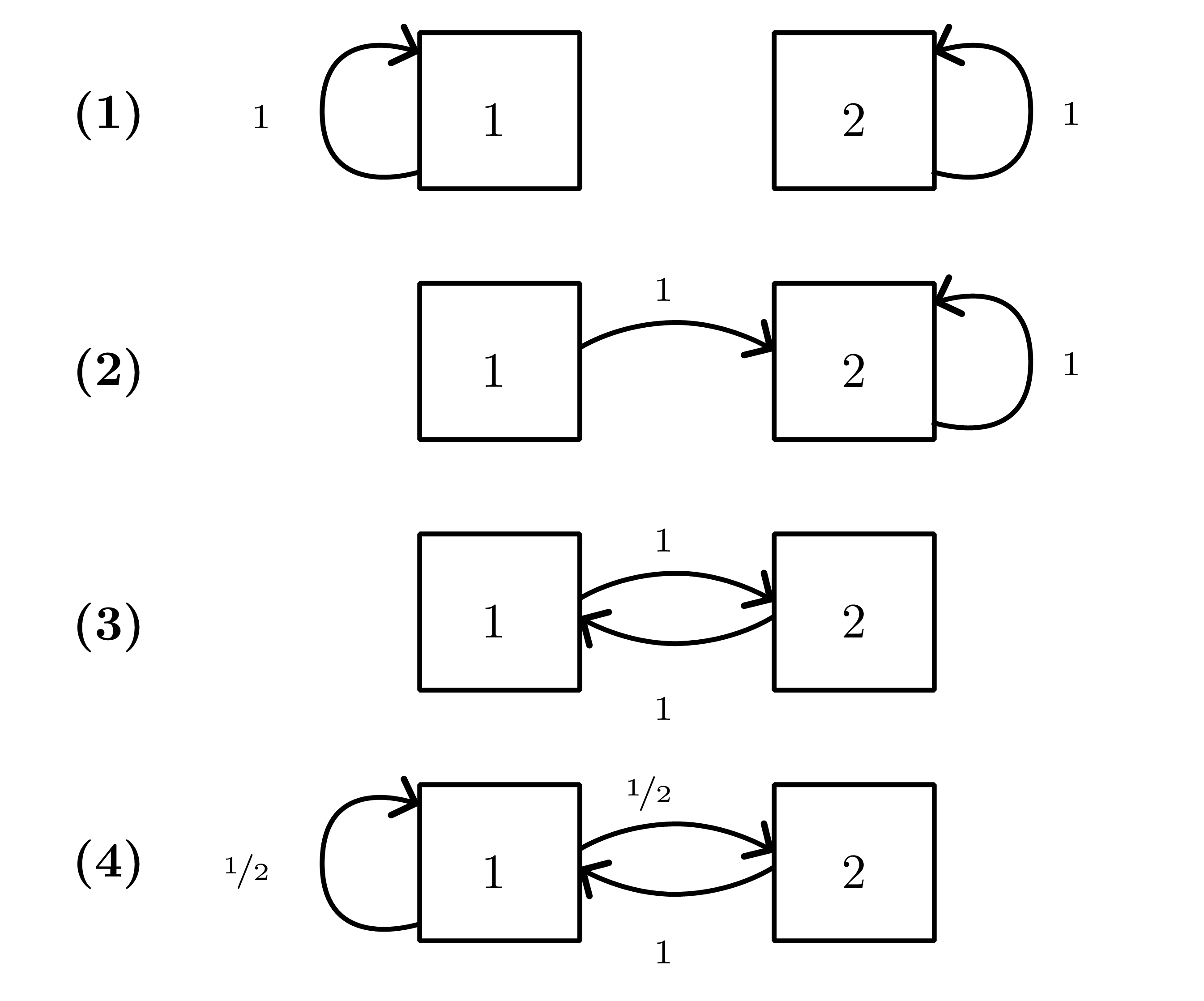

- Homogeneous chain with transition kernel \(P(x'\mid x)\); \(k\)-step transition \(P^k\).

- Stationary distribution \(\pi\) solves \(\pi^\top P = \pi^\top\). If chain is irreducible and aperiodic (ergodic), \(q_t\to\pi\) for any start (Fundamental theorem; see Figure 2 ).

- Detailed balance \(\pi(x)P(x'\mid x)=\pi(x')P(x\mid x')\) suffices for stationarity (reversibility).

- Distance to stationarity measured in total variation \(\|q_t-\pi\|_{\mathrm{TV}}\); mixing time \(\tau_{\mathrm{mix}}(\epsilon)\) ≈ steps to get within \(\epsilon\).

Metropolis–Hastings (MH)

- Goal: target density \(p(x)=q(x)/Z\) (unnormalized \(q\) known).

- Proposal \(r(x'\mid x)\); accept with \[\alpha(x'\mid x)=\min\left\{1,\frac{q(x')r(x\mid x')}{q(x)r(x'\mid x)}\right\}.\]

- Ensures detailed balance w.r.t. \(p\).

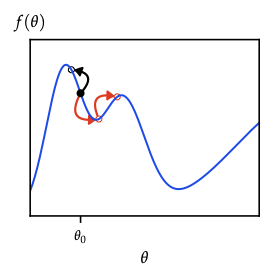

- Tuning: poor proposals ⇒ slow mixing (random walk). Adaptive schemes adjust step size to hit desired acceptance (≈0.234 in high-dims for isotropic random walk).

Gradient-informed proposals

- MALA: \(x' = x + \tfrac{\epsilon^2}{2}\nabla\log q(x) + \epsilon\xi\) (Langevin step) then MH accept; leverages gradient, useful in high dimension.

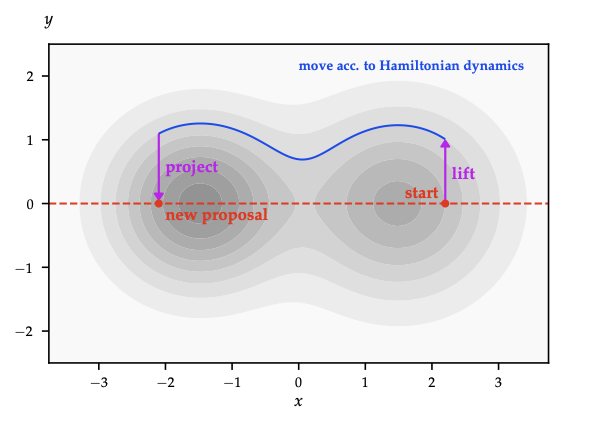

- HMC: introduce momentum \(p\sim\mathcal{N}(0,M)\), simulate Hamiltonian dynamics, accept via MH. Long, low-rejection moves reduce random walk behaviour; requires gradient of \(\log q\).

- Riemannian manifold HMC: adapt metric to local curvature.

Gibbs sampling

- Cycle through coordinates (or blocks): sample \(x_i \sim p(x_i\mid x_{-i})\).

- Special case of MH with unit acceptance. Works when all conditionals easy; order can be fixed or random (random scan preserves detailed balance).

- Block Gibbs improves mixing when variables correlated.

Practical workflow

- Initialize (multiple chains if possible).

- Burn-in until diagnostics (trace plots, potential scale reduction \(\hat{R}\)) stabilize.

- Collect samples, optionally thin to reduce storage (does not improve ESS).

- Estimate expectations via Monte Carlo averages; report Monte Carlo error using ESS or batch means.

Energy interpretation

- Target \(p(x) \propto e^{-E(x)}\) with energy \(E(x)=-\log q(x)\).

- Random-walk MH explores energy landscape slowly; Langevin/HMC follow gradient/level sets ⇒ faster exploration.

- Simulated tempering / parallel tempering mix chains at different temperatures to escape local modes.

When to choose MCMC

- High-fidelity posterior samples needed (e.g., small models with multimodality) and gradient evaluations affordable.

- Combine with VI: use VI for initialization, then MCMC for refinement (e.g., Laplace+MCMC).

- Expensive in high dimension; mixing diagnostics essential.

MCMC keeps normalization outside the loop; designing good proposals is the art. Understanding irreducibility, acceptance ratios, and diagnostics is crucial before scaling to Bayesian deep learning or world-model uncertainty.